What's the big idea?

Yes, that question we hate

The concept behind this newsletter was, among other things, to look at every stage of writing a book and the tools and techniques I use to get a novel down on paper. There’s the Basic 500, of course, but essentially that’s just turning up every day. There’s a whole lot of other infrastructure I have in place to project manage a book. Some of it is niche or perhaps even unique to me, some of it is what everyone does.

But every novel starts in the same place: with an idea.

Famously, most writers hate being asked where they get their ideas. We hate being asked that because we hear it so often, and because there’s no a satisfactory answer.

I thought it might be useful to talk a little about about something slightly different: how I wrangle the ideas, and more importantly, how I work them up into a book.

I spoke in the previous newsletter about how I developed my new book 138 Main from a kernel of an idea to a full novel (which is available to pre-order now).

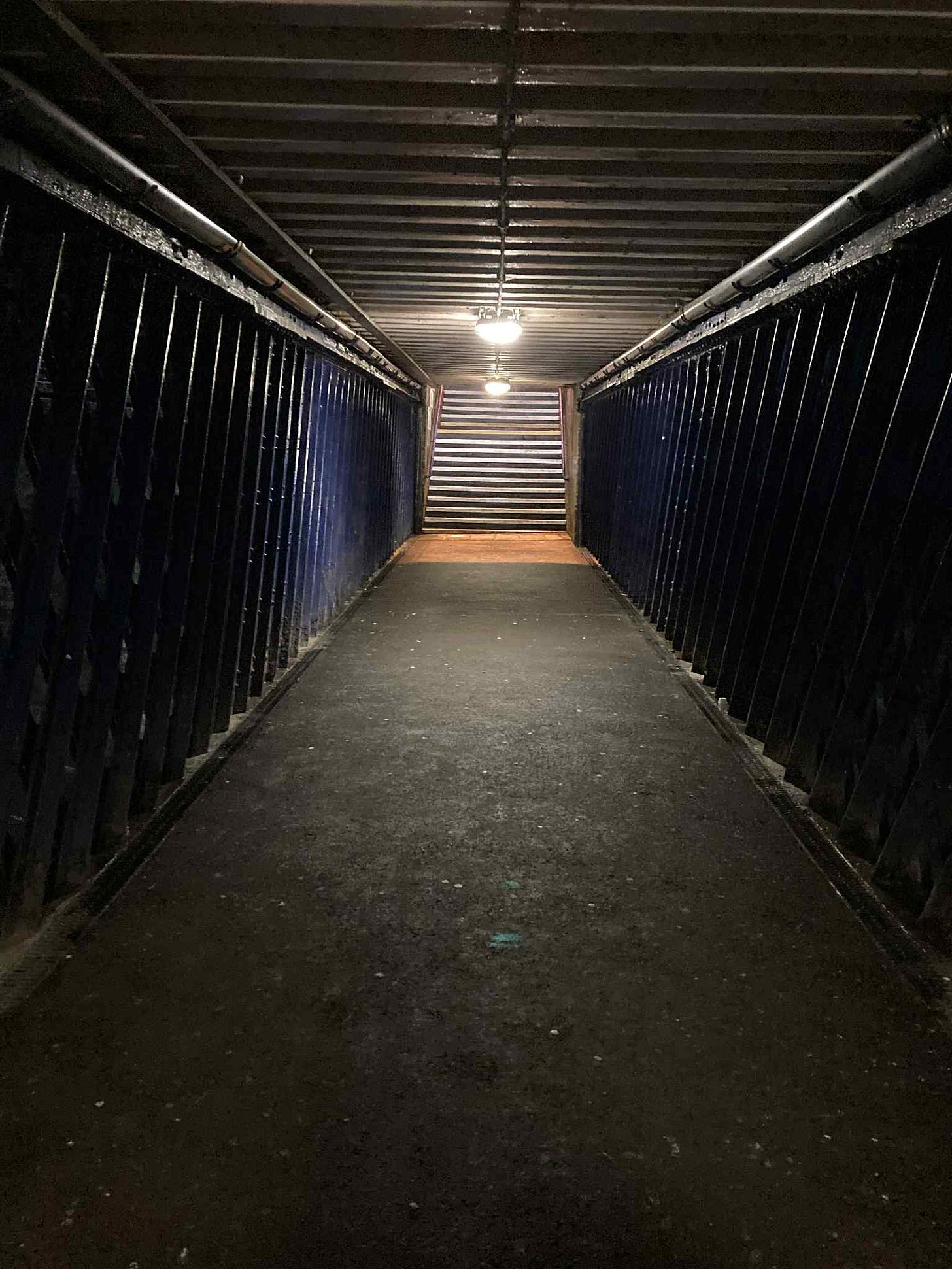

So to deal with the ‘where do you get your ideas’ question at face value: I get ‘em from lots of places. News stories, magazine articles, other books, life, overheard comments in a restaurant, daydreaming on a platform waiting for a late train. Ideas are a dime a dozen - it’s knowing which ones have legs that takes work.

To do that, it’s often important to give your ideas some time and distance and then come back to them with fresh eyes. Which, come to think about it, is one of the literal answers to ‘where do you get your ideas’ - why, from my ideas file.

I used to jot down story ideas in notebooks. Still do, sometimes. The problem with that is that I have at least half a dozen half-filled notebooks on the go at any one time. And often, none of them are to hand, so I have plenty of ideas written down on the back of the agendas from boring meetings, on hotel notepaper, and yes, sometimes even on the back of an envelope.

I’m not the first to observe this, but writing an idea down before it floats away into the ether is important. Sometimes they don’t go anywhere, but sometimes you’ll come back to it and see an angle of attack.

These days, for that quick get-it-down moment, I use my phone, specifically the Google Keep app. A phone is, for better and worse, always close to hand, so that’s a good way to do it.

Using a notes app like Keep has many advantages over paper - it’s all in one place, it’s immediately backed up and accessible from other devices, and it’s searchable. I like Keep because it’s a bit like having lots of Post-It notes in front of you, but without the mess.

I have an ongoing note where I can add single-line bullet point ideas and refer back to it for inspiration. While I’m working on a novel, I’ll have notes to work out specific ideas on that book. I can categorise, save photos, add links to relevant web pages, make each project a different colour. When I’m working through an edit, I make a new note that’s a checklist of major points to address and check them off as I fix each one.

I still use paper notebooks, but more for the structured brainstorming part - when I’m starting to flesh out an outline, or when I’m stuck at 60,000 words and need to write myself out of a corner. Pen and paper definitely engages a different part of your brain from keys and screen, and I find the tactility helps me to break down problems more easily. You also get a real-life Track Changes function by looking at what you’ve scribbled out or drawn a line through.

Often, you really get somewhere by mixing and matching different ideas that you might have jotted down years apart. I referred earlier to getting an idea for my latest book, 138 Main, but as I discussed last time around, it was really two ideas that fit together: an intruder targeting unremarkable suburban dwellings, and the problem of knowing which address you want to protect when there are over 7,000 homes sharing that address.

Two ideas fitting together has been the genesis of several of my books - a professional people finder who has to find one of his former colleagues went together nicely with an idea about a serial killer who causes cars to break down on isolated roads. Together it gave me a great setup for The Samaritan.

Those unlikely chance encounters where you run into someone you haven’t seen in years in an unlikely location meshed with a new spin on a witness protection thriller in Darkness Falls.

It doesn’t always happen that way, but it’s something that works for a lot of writers. Ideally, what you want is for the two ideas to contrast, but complement each other, giving you a uniqe angle on a story that anybody else might have come up with.

So if you’re struggling for ideas for a new project, go back to your list of random thoughts and see if two or three of them might go together.

And write stuff down, so you have that list in the first place.

Pre-order my new novel 138 Main here.

Reading

Stuart Neville’s Blood Like Ours is the second in his noir-road-movie-vampire trilogy. It’s taken me since the summer to get to this, but it was worth the wait.

Watching

I was about to start watching the new season of The Night Manager when I realised I couldn’t remember much about season one, other than I enjoyed it. This isn’t my fault, because taking ten years between seasons is going a bit far even by the leisurely standards of the Stranger Things showrunners. Anyway, I thought I’d watch episode one of the original again and binged the whole thing in a couple of days. Interesting to revisit it after reading the original novel by John Le Carre a couple of years ago.

Writing

Back into the swing of the new novel following the Christmas break. I made sure I got the basic 500 down most days last week, and now I’m aiming for at least 1,000 words plus a day. All being well I’ll have a draft by February which I can then go back and rip apart. You can fix a draft, you can’t fix a blank page.

Listening

I’m always on the lookout for music to write books to. Mark Isham’s hybrid orchestral/synth score for Point Break seems to be impossible to buy physically, but it’s on YouTube, and I love it. The most underrated aspect of a classic film.

See you in fourteen…